A new Yale study, “Mucosal Unadjuvanted Booster Vaccines Elicit Local IgA Responses by Conversion of Pre-Existing Immunity in Mice,” suggests nasal vaccine boosters can trigger strong immune defenses in the lungs and airways to protect against respiratory diseases. Researchers said the findings, published in the journal Nature Immunology, may offer critical insights into developing safer, more effective nasal vaccines in the future.

Akiko Iwasaki, PhDYale School of Medicine

Akiko Iwasaki, PhDYale School of Medicine

Using mouse models, researchers first administered a traditional mRNA COVID-19 shot, which was injected directly into the muscle. Then, the team gave mice a booster vaccine through the nose. The objective of the study was to evaluate the effects of vaccine boosters that don’t contain adjuvants, a common vaccine ingredient that helps stimulate a stronger, longer-lasting immune response but can also cause adverse events like inflammation and swelling of facial nerves.

“We call this vaccine strategy ‘prime and spike,’ which is where the mice were intramuscularly primed with mRNA vaccines followed by a nasal boosting with unadjuvanted spike protein,” said first author Dong-il Kwon, a postdoctoral fellow at Yale School of Medicine and member of Dr. Iwasaki’s lab.

According to a university press release, “prime” refers to the traditional intramuscular shot and “spike” refers to the follow-up nasal vaccine, typically delivered as a spray containing coronavirus-derived spike proteins.

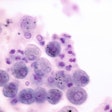

The Yale-developed approach essentially jumpstarts an immune response in the respiratory system — the first area in the body to be infected by COVID-19. After the first shot, immune cells in the mice became primed in the lymph nodes. After the nasal booster, B cells from the lymph nodes migrated to the lungs and produced immunoglobulin A (IgA), an antibody that protects the nose and lungs from infection.

Researchers found only the nasal booster triggered a strong local immune response, where memory CD4+ helper T cells acted as natural adjuvants by recruiting B cells and helping them secrete IgA in the lung. The intramuscular injection did not produce much IgA or activate immune cells in the lungs of the mice. When researchers gave the mice a second nasal booster, IgA levels increased even more in both their lungs and nasal passages.

“These findings help explain why nasal boosters do not require adjuvant to induce robust mucosal immunity at the respiratory mucosa and can be used to design safe and effective vaccines against respiratory virus pathogens,” Kwon said.

This study will aid future research to create a similar approach that can be used in humans, said Dr. Iwasaki.