New findings published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine revealed a harmful implication of inhaling microplastics. The tiny pollutants impede pulmonary macrophages, which are a type of white blood cell critical to the immune system.

The abstract, “Inhaled Microplastics Inhibit Tissue Maintenance Functions of Pulmonary Macrophages,” further highlights the damages of human exposure to microplastics.

First author Adam Soloff, PhD, presented research highlights at the American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2025 International Conference. Dr. Soloff is associate professor of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania.

Adam Soloff, PhDUniversity of Pittsburgh

Adam Soloff, PhDUniversity of Pittsburgh

Among these risks are long-term impairment of the immune system and an increased risk of lung cancer. Suppressed pulmonary macrophages aren’t able to properly ward off pathogens, preserve lung tissues and purge dead cells that, if left to accumulate, can cause chronic inflammation or infection.

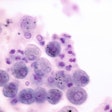

In the study, researchers observed mouse models that had been exposed to inhaled microplastics and measured their macrophage function to determine the impact. The team also analyzed cultured macrophages with different amounts and concentrations of polystyrene microplastics.

Within 24 hours of microplastic exposure (regardless of size or strength), the macrophages displayed reduced function to encircle and eliminate other bacteria — a central process called phagocytosis. Up to a week after exposure, researchers detected moderate to trace amounts of microplastics in numerous mouse organs, including the liver, spleen, colon, brain, kidneys and lungs.

“I was really surprised to see that not only did the macrophages struggle to break down the plastics in vitro, but macrophages in the lung retained these particles over time as well,” said Dr. Soloff.

On a positive note, the researchers discovered that introducing the drug Acadesine, an AMP kinase activator, after microplastic exposure helped to partially restore pulmonary macrophage function. The breakthrough supports the use of Acadesine or similar drugs in high-risk populations to reduce or reverse damage.

“Given the poor air quality in so many places around the world, you could imagine that developing a low-cost, low-side effect therapeutic to restore pulmonary macrophage function may be an important tool to combat increasing rates of lung disease.”

Dr. Soloff said the study results could also influence global public health measures aimed to reduce the use of and exposure to microplastics. He and his team plan to examine the effects of microplastic exposure in human lung tissue and hope to identify biomarkers for lung cancer and diseases that could aid early diagnosis and intervention.