Researchers and physicians at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) in New York City have discovered a new, rare type of small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Their findings were published in Cancer Discovery. The team reported that the identified subtype, known as atypical small cell carcinoma, primarily affects younger non-smokers.

Natasha Rekhtman, MD, PhDMemorial Sloan Kettering

Natasha Rekhtman, MD, PhDMemorial Sloan Kettering

The group of 42 experts included doctors and clinicians who focus on lung cancer, as well as pathologists who examine cells and tissues to aid in diagnosis and researchers who specialize in tumor genetics and computational analysis.

“Understanding this new type of lung cancer required a broad spectrum of expertise from the laboratory to the clinic,” said Charles Rudin, MD, PhD, a lung cancer specialist and senior author of the study.

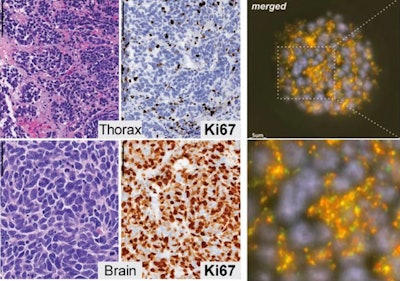

Unlike standard SCLC, which is depicted by inactive RB1 and TP53 genes that normally protect against cancer development, atypical small cell carcinoma was found to have these genes intact. Rather, the majority of patients who identified with the rare subtype possessed a notable “shattering” of one or more chromosomes in their cancer cells — a phenomenon called chromothripsis.

“We often talk about cancer as an ongoing buildup of mutations, but this cancer has a very different origin story,” said Dr. Rekhtman. “With chromothripsis, there’s one major catastrophic event that creates a Frankenstein out of the chromosome, rearranging things in a way that creates multiple gene aberrations, including amplification of certain cancer genes.”

According to the American Cancer Society, small cell lung cancer accounts for 10% to 15% of all lung cancers. The new study evaluated 600 patients with SCLC, of which only 20 people (3%) had the rare subtype. Thirteen patients had never smoked, and the other seven reported a history of light smoking (less than 10 years). Although the average age at diagnosis was 53, which is considered young for people with lung cancer (compared to the standard average of 70 years old), the first patient diagnosed with the condition was only 19 years old and a non-smoker.

Khaliq Sanda was a sophomore at Duke University when he initially got diagnosed with small cell lung cancer. His profile was unusual for the disease, and it flagged doctors to take a closer look at the cause.

Charles Rudin, MD, PhDMemorial Sloan Kettering

Charles Rudin, MD, PhDMemorial Sloan Kettering

The researchers said atypical small cell carcinoma likely occurs when low-grade neuroendocrine tumors (pulmonary carcinoids) transform into more aggressive carcinomas. Due to these unique genomic variations, they said it is unlikely that standard, first-line, platinum-based chemotherapy treatments will work. Alternative therapeutic strategies, such as investigational drugs that can target extrachromosomal circular DNA, may prove more beneficial.