Researchers from Rockefeller University and Insitut Imagine unexpectedly discovered the source of a rare disease while searching for evidence of genetic deficiencies that might alter the behavior of certain immune cells in the lungs. Results of the advancement were recently published in Cell.

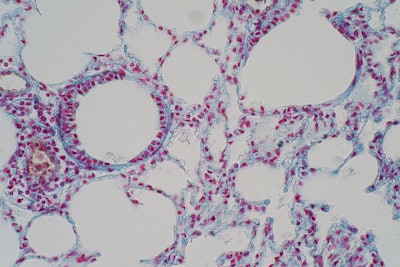

During the study, investigators zeroed in on a small group of children, each of whom had suffered from numerous severe illnesses affecting their ability to breathe, including pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP), progressive polycystic lung disease and chronic bacterial and viral infections. All nine children were also missing about half of their alveolar macrophages as well as a chemical receptor called CCR2, or C-C motif chemokine receptor 2. The function of this receptor is to activate the macrophages located in the air sacs of the lungs.

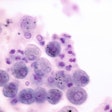

A macrophage is a type of immune cell that rids harmless particles, like dust, debris and dead cells, and kills off pernicious elements like cancer cells. Within the lungs, alveolar macrophages help control surfactant levels and fight infection.

Upon discovery, the scientists assessed the children’s clinical histories, lung tissue samples and genetic data. They determined that the absence of CCR2 caused there to be an excess of the binding molecule CCL-2, or C-C motif chemokine ligand 2. Without its receptor, CCL-2 causes buildup in blood and plasma. Prior to this study, CCR2 had never been linked to disease.

“It was surprising to find that CCR2 is so essential for alveolar macrophages to properly function,” said author Jean-Laurent Casanova, MD, PhD. “When it comes to lung defense and cleanup, people without it are operating at a double loss.”

Dr. Casanova is a Levy Family Professor at Rockefeller University in New York City and a lead researcher at Institut Imagine in Paris. According to him, the findings show potential in creating a diagnostic test to screen patients who have unexplained lung of mycobacterial disease. Early detection of the genetic malfunction would allow for proper treatment and reduce the risk of severe complications.

The research team plans to conduct further research to better understand the development of the disease. Lead author Anna-Lena Nehus said: “With more follow-up studies, we could potentially cure the patients by using gene therapy to correct the mutation.”