Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, are on the road to better understanding a major cause of chronic lung disease. The study, which was published in Nature Microbiology, reasons that respiratory viruses linger in the body long after symptoms of the initial infection are gone. Previously, a direct link between chronic lung disease and ongoing viral presence had not been shown, according to senior author Carolina B. López, PhD.

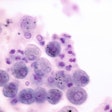

“Finding persistent virus in immune cells was unexpected. I think that’s why it had been missed before,” said Dr. López, professor of molecular microbiology and a BJC investigator at WashU Medicine, in a university news release. “Everyone had been looking for viral products in the epithelial cells that line the surface of the respiratory system, because that’s where these viruses primarily replicate, but they were in the immune cells.”

To examine the suspected connection, the research team introduced a natural mouse virus in mouse lung models. The behavior of Sendai virus in mice is similar to human parainfluenza, a common respiratory virus that, along with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), is associated with the development of chronic conditions like asthma and COPD.

“We used a perfectly matched virus-host pairing to prove that a common respiratory virus can be maintained in immunocompetent hosts for way longer than the acute phase of the infection, and that this viral persistence can result in chronic lung conditions,” said Ítalo Araújo Castro, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher and first author of the study. “Probably the long-term health effects we see in people who are supposed to be recovered from an acute infection are actually due to persistence of virus in their lungs.”

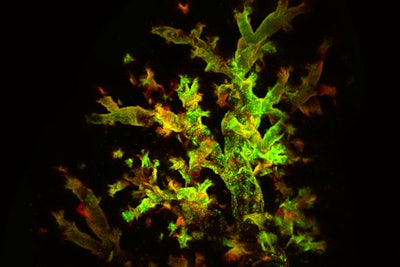

The researchers used fluorescent markers to identify where the virus was still present as well as where it had replicated. Although symptoms had resolved and the mice appeared to be in recovery, they found traces of the virus hidden in immune cells in the lungs, creating a persistent inflammatory environment. Even up to seven weeks after infection, there was inflammation of air sacs and blood vessels as well as excess immune tissue and abnormal development of lung cells — all signs of chronic lung damage.

“Right now, children who have been hospitalized for a respiratory infection such as RSV are sent home once their symptoms resolve,” Dr. López said. “To reduce the risk that these children will go on to develop asthma, maybe in the future we will be able to check if all of the virus is truly gone from the lung and eliminate all lingering virus before we send them home.”

To Dr. López’s point, once the infected cells were removed, inflammation decreased and signs of lung damage faded. These findings indicate the need for a new approach to detecting and managing respiratory viruses and chronic lung conditions.

“Pretty much every single child gets infected with these viruses before the age of three, and maybe 5% get serious enough disease that they could potentially develop persistent infection,” she said. “We’re not going to be able to prevent children from getting infected in the first place, but if we understand how these viruses persist and the effects that persistence has on the lungs, we may be able to reduce the risk of serious long-term problems.”