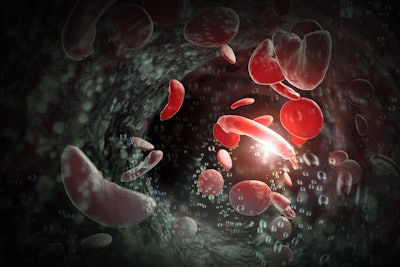

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) released promising results for people who have sickle cell disease (SCD). In the three-year study, NIH evaluated adult patients who underwent a low-intensity blood stem cell transplant. Some patients saw improvement in lung function, and NIH found no apparent lung damage as an outcome of the procedure.

The new study, published in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society, will help determine how adults tolerate the less intensive transplant and if the treatment causes or promotes additional harm to the lungs.

“By using a low-intensity blood stem cell transplant for sickle cell disease, we may be able to stop the cycle of lung injury and prevent continued damage,” said lead author Parker Ruhl, MD, an associate research physician and pulmonologist at NIH.

According to the researchers, at least one-third of sickle cell stem cell transplants performed are low-intensity. Although they are slightly less effective than standard transplants, adults with more pre-existing organ damage often have better outcomes and fewer complications, such as graft-versus-host disease. This study also examined if this type of transplant provided additional benefits for adults with already vulnerable lungs.

Dr. Ruhl and her team studied 97 patients with SCD who had a low-intensity, or non-myeloablative, blood stem cell transplant between 2004–2019 at the NIH’s Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. The team continued to monitor the patients for up to three years by conducting various pulmonary function tests, including forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV-1), lung diffusion (DLCO) and six-minute walk distance.

The average overall lung function of the patient cohort remained stable over the course of the three-year period. DLCO levels and six-minute walk distance significantly improved post-transplant. FEV-1 levels remained relatively unchanged, indicating that lung function did not worsen following the procedure.

“Without the ongoing injury, it’s possible that healing of lung tissue might occur, and this finding should help reassure adults living with sickle cell disease who are considering whether to have a low-intensity stem cell transplant procedure that their lung health will not be compromised by the transplant,” Dr. Ruhl said in a NIH news release.

Historically, the only cures for SCD were blood stem cell and bone marrow transplants from donor matches. These procedures are often associated with chemotherapy to prepare for the transplants and carry high health risks. In December 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved two genetic therapies that use a patient’s own blood stem cells to treat SCD.

Dr. Ruhl said she hopes the techniques used in this NIH study and the optimistic outcomes will prompt additional studies with larger, more diverse populations and longer follow-up periods to further assess lung function and develop other new genetic therapies.