During specialization, individual cells form different airway cell types, a process that can include a period of uncertainty, although they are seemingly coded to develop specific airway cells. This uncertainty helps cells to specialize but also respond to an ever-changing environment.

These are the findings presented by an international team of researchers led by Kedar Natarajan, PhD, associate professor at DTU, published in Science Advances. “This discovery may have the potential to be good news for patients with dysregulated airway cell types, including in asthma, COPD and cystic fibrosis,” said Dr. Natarajan.

Human beings consist of trillions of cells composed of several cell types performing specialized roles within organs. How the cell types, particularly specialized cells in the airways, are formed during the early phase of embryo formation (embryonic development) is of interest for chronic diseases and therapy.

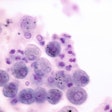

Researchers have used new state-of-art sensitive technologies as well as sequencing and computational methods to understand the process of how these cell types are formed during the early phase of embryo formation, and they have found evidence of a non-standard model, wherein cells in a continuous non-hierarchical manner undertake decisions, unlike in other well-studied systems.

“Our time-course analysis of embryonic development captures a new progenitor, i.e., parent cell population in the mucociliary epithelium, such as the airway, composed of different cell types like basal cells, ionocytes and goblet cells. This progenitor population occurs much earlier than expected and contributes to the formation of all major cell types, highlighting the crucial role of cellular heterogeneity before committing to a specialization. This means that the decision for some cell types is made long before we can see it,” said Dr. Natarajan.  Kedar Natarajan, PhD

Kedar Natarajan, PhD

Chronic respiratory diseases are a major killer worldwide

The researchers have studied a specific type of progenitor cell from tissue in the respiratory tract, the so-called mucociliary epithelium. The molecular mechanisms enabling cells to specialize over time during mucociliary epithelial development have been relatively less explored until now.

The different cell types provide natural immunity and remove pathogens, dust and other particles from the airway tract while maintaining optimal osmotic, ionic and acid-base levels. The formation and function of the specialized cells are affected in people who suffer from respiratory diseases, such as asthma and COPD. These chronic diseases can today be alleviated, but there is still no cure. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), respiratory problems are responsible for about 15% of all deaths. These include diseases such as asthma and COPD, but also cancer, pneumonia and cystic fibrosis. WHO estimates that 339 million people worldwide are affected by asthma alone.

“To understand what happens when chronic respiratory diseases occur, we need to have a better picture of all the states the cell goes through, especially during the early stages of cell type formation. We often study what happens to a cell after it has gone bad, and then try to repair it. We should also study how the cell is formed to better understand how it is broken. The body’s cells renew themselves all the time, so when we know how the cell’s decision can be influenced along the way, that knowledge can help open a new door to how we treat diseases like asthma or COPD,” explained Dr. Natarajan.

“Our work provides an insight into the changes in the state of the cells that occur when the mucociliary tissue develops. It helps to dissect the mechanisms involved during the formation of the tissue. And this knowledge can be useful in developing regenerative treatments for chronic lung diseases, for example,” he said.

Cell transformations have been studied in frogs

The researchers have taken the mucociliary cells of the Xenopus frog as their starting point. The development in the frog’s cells is similar to that of the mucociliary cells in humans. The difference is that it is easier to distinguish the four directions in which the cells develop in the pluripotent cells.

The researchers have mapped the development of each cell at 10 different developmental stages, starting from undifferentiated cells (stage 8) all the way to differentiated cells (stage 27), where major cell types are formed for specific functions. Interpreting how cells differentiate across all stages is like understanding a highly elaborate family tree, analyzing what differs from generation to generation.

In total, the researchers studied approximately 35,000 cells and evaluated approximately 3,000 genes for each cell. This resulted in enormous amounts of data that made the researchers aware that some of the cells go through a previously unknown state (termed "early epithelial progenitors") and undergo specialization in a distinct manner.

“During our work, we discovered a progenitor population that we believe was previously missed. We call the cells the early epithelial progenitors. They undertake specialization to form late-stage ionocytes, goblet cell and basal cell populations. Therefore, we propose a model wherein early epithelial progenitors undergo fate transitions in a continuous non-hierarchical manner that is distinct from the standard model,” said Dr. Natarajan.