Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (UPSM) in Pennsylvania, who were searching for the underlying genetic and molecular causes of asthma, recently discovered a connection between mitochondrial ferroptosis and the respiratory condition.

In their study, “Compartmentalized Mitochondrial Ferroptosis Converges With Optineurin-Mediated Mitophagy to Impact Airway Epithelial Cell Phenotypes and Asthma Outcomes,” researchers concluded that mitochondrial changes are central to the development of an abnormal epithelium observed in asthma. According to lead researcher Sally E. Wenzel, MD, professor of medicine and immunology at UPSM, that is a novel finding. Dr. Wenzel also serves as chair of USPM’s School of Public Health, department of environmental and occupational health and director of its Asthma and Environmental Lung Health Institute.

Sally E. Wenzel, MD

Sally E. Wenzel, MD

Dr. Wenzel said the study, which was published in Nature Communications, sought to determine if a portion of that oxidative stress was related to changes in the mitochondria — the engines that power nearly all living cells. Mitochondria allows cells to proliferate, make proteins and differentiate.

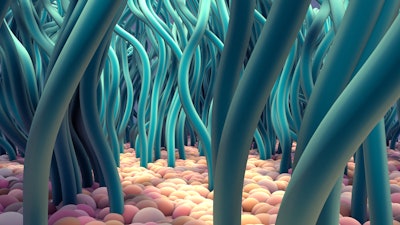

Part of mitochondria’s role is to power short, hair-like structures, called cilia, to clear the airways of debris and microbes. This function protects the lungs from infection and breathing problems.

“For many years, we’ve been studying a cell-death pathway called ferroptosis. In this new study, we were curious if ferroptosis was activated in asthma and asthma-like conditions, leading to mitochondrial damage, which would prevent the development and function of these ciliated cells,” Dr. Wenzel said.

Researchers further hypothesized that autophagy was occurring in mitochondria. Although recycling mitochondria could be helpful, she said, this action could also contribute to the struggle of “stressed-out” cells in the epithelium.

“Could these mitochondrial changes be contributing to removing, or even killing, the housekeeping ciliated cells?” she asked.

Using bronchoscopy, the team collected and examined human airway epithelial cells sampled from patients with asthma and without. After culturing the cells and observing them in action, the researchers discovered that in asthmatic patients, ferroptosis targeted mitochondria for destruction. This interfered with the development of ciliated cells. In fact, ciliated cells were absent in patients with severe asthma, occurring in conjunction with mitochondrial damage. According to Dr. Wenzel, the degree of loss was related to the severity of obstruction in the bronchial tubes in people with asthma.

Researching mitochondrial changes and accompanying factors may offer new targets for potential asthma therapies, she said. Improving mitochondrial health, or even preventing the initiation of the damage, could prevent the development of asthma and improve asthma outcomes.

“We are trying to better understand what is happening to the mitochondria, how widespread the damage is and whether factors like smoking, pollution and viruses aggravate it,” Dr. Wenzel said. “In the case of viruses, these damaging processes could be hijacked to increase viral replication and lead to exacerbations of asthma that we see so commonly in children and adults with this chronic illness.”