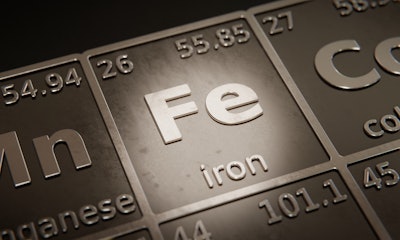

Iron may be a driving force behind inflammation associated with an allergic asthma attack. And developing a therapy that blocks or limits the mineral may hold the key to reducing symptoms.

That discovery comes from researchers at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine in Los Angeles. According to the study, “Iron Controls the Development of Airway Hyperreactivity by Regulating ILC2 Metabolism and Effector Function,” published in Science Translational Medicine, group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) inside the lungs may be iron-sensitive, becoming overactive and causing excessive inflammation.

“This is the first time it’s been shown that iron is an important metabolic regulator of pulmonary immune cells such as ILC2s, allowing them to generate energy,” said Benjamin Hurrell, PhD, a research assistant professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Keck School of Medicine and lead author of the study. “That’s helpful for treating disease, because targeting a cell’s energy can allow us to selectively increase or decrease its function.”

When ILC2s become overactive, the increasing inflammation leads to a tightening of the airways and makes it difficult to breath. Until now, the underlying biology has been a mystery. Now knowing that ILC2s need iron to generate energy, researchers believe they can use that information to develop treatments that target asthma and other allergic diseases.

The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, involved a series of tests on both human cells and mouse models. They learned that ILC2s use iron to fuel a range of cellular processes, making it instrumental in activating the immune cells. In mice, preventing iron uptake in ILC2s reduced the severity of asthma symptoms. In human cells, increased ILC2 activity and iron uptake were associated with asthma severity. This suggests that ILC2s and iron play a key role in more serious cases of the disease.

“We have limited drugs besides steroids for patients with asthma,” said Omid Akbari, PhD, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Keck School of Medicine and the study’s senior author. “Steroids, inhalers and pills can control symptoms to keep patients alive, but they are not attacking the underlying pathophysiology of the disease.”

Researchers first had to understand the role of iron in asthma. To gain that understanding, they conducted a series of mechanistic studies — scientific investigations of the fundamental molecules, pathways and genes that underlie various biological processes.

Iron enters cells by binding to a protein called transferrin. Researchers used a traceable form of transferrin, then activated ILC2 cells with an allergen. They observed transferrin entering the cells, proving that iron was also being taken up. When the researchers blocked ILC2 cells from absorbing transferrin (and iron), ILC2 activity dropped

Blocking transferrin receptors is one way to prevent iron uptake in cells, but the researchers also tested their theory using another method: a substance called a chelator, that can bind to iron and restrict its availability for cells. The team used deferiprone, an iron chelator used to treat patients with a condition known as hemochromatosis, or iron overload. When they added deferiprone to cultured ILC2s, the result was the same: Iron availability decreased and so did ILC2 activity.

Next, the research team used single-cell RNA sequencing to analyze the transcriptomes of ILC2 cells. That analysis revealed that iron is a key part of the pathway for energy production in ILC2 cells.

In addition to mechanistic studies, the researchers tested the effect of limiting cellular iron availability in mouse models. Mice who received an iron chelator had less lung inflammation and airway hyperactivity — key features of asthma — compared to mice in a control group. In the absence of iron, ILC2s must adapt and generate energy in other ways, Hurrell said, which are associated with lower inflammation.

Finally, the team used cells from 36 patients with different asthma severities to further confirm that their findings will be useful for patients. They again showed that blocking iron uptake reduced the activation of ILC2 cells. They also found that cells from some donors had higher expression of a transferrin receptor, causing ILC2s to absorb more iron. That feature was correlated with more severe asthma, confirming a direct link between iron uptake and asthma in humans.

“We can’t deplete a biological system of iron, which is an essential element for transporting oxygen in the body,” Dr. Akbari said. “But restricting iron availability to immune cells in the lungs could reduce the exacerbation of asthma during an acute attack. This approach also paves the way for treating other lung immune-mediated and inflammatory diseases, such as COVID-19.”

Researchers said their findings also could help provide relief for other allergic diseases, including eczema, dermatitis, hay fever, rhinitis and food allergies, in which ILC2 cells also become hyperactive.