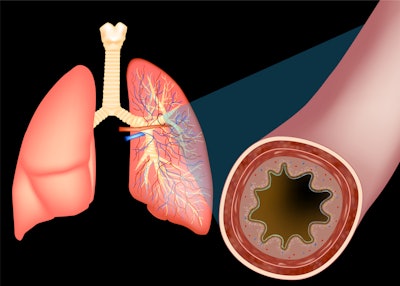

A new study from researchers at Mass General Brigham health care system in Boston has uncovered another factor linked to the progression of COPD: the accumulation of mucus in the lungs.

The study, “Longitudinal Changes in Airway Mucus Plugs and FEV1 in COPD,” published in The New England Journal of Medicine, found that COPD patients who had persistent, airway-clogging mucus plugs over a five-year period had a faster decline in lung function than those without the plugs.

According to a news release, the study points the way to therapies that disrupt these plugs as a promising strategy to slow down the progression of the disease and improve the quality of live for those patients.

“Mucus plugs can come and go. In some people they resolve, and in others they seem to stick around,” said lead study author Sofia Mettler, MD, MSc, a clinical fellow in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH). “If the mucus plugs resolve, the patients have a slower lung function decline than those who have a persisting block.”

Senior author Alejandro Diaz, MD, MPH, of the BWH Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, said his research team previously published a paper that observed the correlation, even in patients who were not experiencing symptoms like cough and phlegm production. It was this paper, “Airway-Occluding Mucus Plugs and Mortality in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease,” that led the researchers to figure out how the persistence or resolution of mucus plugs can influence the progression of the disease.

They examined data from 2,118 participants in the COPDGene study (financed by the National Institutes of Health), which included participants’ forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) — a measure of lung function. The study looked at whether the mucus plugs were present, including evidence of the plugs on CT scans at two timepoints: the initial assessment and a follow-up conducted five years later.

The researchers found the group of patients with persistent mucus plugs (present at both assessments), and the group that had newly developed plugs by the follow-up assessment, had significantly faster lung function decline compared to the group that did not have mucus plugs at either time. Those individuals whose mucus plugs were present at the initial screening but had resolved by the follow-up showed no difference in lung function decline compared to those without mucus plugs at either time.

“Because it is an observational study, we cannot conclude a causal relationship,” Dr. Mettler said. “So, the next logical step is to conduct a clinical trial to see if mucus plugs are really what’s responsible for the change in lung function decline.”

The team also plans to uncover what biochemical, demographic, or other extrinsic factors are causing some people’s mucus plugs to resolve and identify potential interventions that can help fight the progression of the disease.